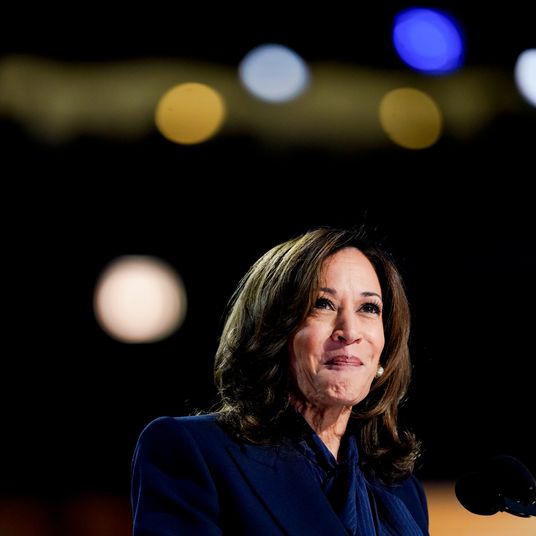

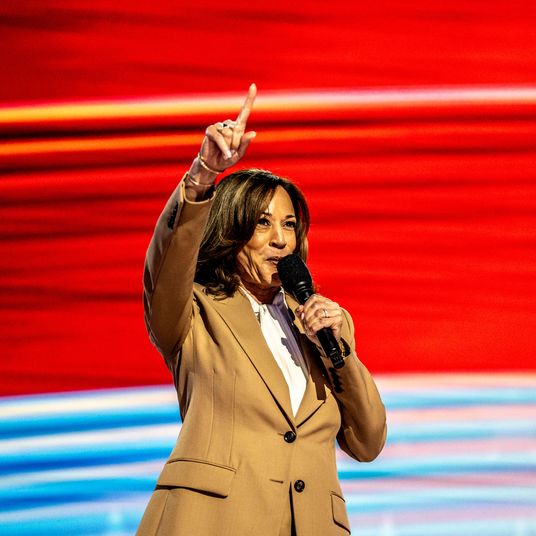

Kamala Harris is announcing a new plan to lower costs for American families. If I had to draw a Venn diagram of the plan — Harris is known to adore Venn diagrams — it would consist of two circles. One would be “proposals that reduce inflation.” The other would be “proposals that are good.” There would be no overlap.

The “good” circle of Harris proposals consists largely of familiar Democratic Party plans to shore up the welfare state. Harris’s plan would increase the child tax credit from $2,000 to $3,000, plus $6,000 per child in the baby’s first year. She would extend enhanced subsidies for purchasing health insurance on the individual market, which makes health care affordable for workers who are too affluent for Medicaid but can’t don’t get insurance from an employer. (Those subsidies are set to expire in 2025.) Harris would also increase the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income workers who don’t have children.

Harris also proposes to expand the administration’s power to negotiate the cost of prescription drugs, which the Inflation Reduction Act created in embryonic form. That lowers the cost of medication for consumers, and also saves money for taxpayers.

The final good idea in Harris’s plan is to increase the supply of housing. Housing costs have risen primarily because local regulations make it difficult or impossible to build housing in places people want to live. Solving the NIMBY (“not in my back yard”) problem is difficult, especially at the federal level, because the opposition occurs mostly in the form of local zoning regulations. But there is a federal role in giving states and cities an incentive to cut the red tape and permit more housing construction.

These are all solid ideas to boost living standards for people who are either poor or fall through the cracks in the safety net, or, in the case of housing, to eliminate a costly market distortion. You’ll notice, however, that these ideas have nothing to do with inflation. They are ideas that were generated when inflation was still low, and they make sense regardless of what the Consumer Price Index happens to be at any given moment.

The other circle of ideas is targeted more directly at prices. The trouble is that these ideas are pretty bad. Harris would raise taxes on major investors who acquire large numbers of single-family rental homes. This is the product of a weird populist fixation with Wall Street buying up homes and renting them out. Creating a larger rental market for single-family homes does not drive up the cost of housing.

Harris would also “crack down on unfair mergers and acquisitions that give big food corporations the power to jack up food and grocery prices.” It may be true that some grocery stories collude to illegally raise prices, but price-fixing is not a major cause of food prices. The grocery industry had a 1.18 percent net-profit margin last year — which is to say, that even if Harris’s plan could somehow eliminate all profits in the industry, consumers would barely notice.

The underlying dilemma reflected in this combination of proposals is that Americans are confused. People are angry about inflation that occurred in 2021 and 2022, and polls show that Americans still believe inflation is rising, even though it is falling to the point where the Federal Reserve is now signaling it intends to cut interest rates.

But political consultants believe telling people the truth, that inflation has receded, doesn’t work. What seems to work, instead, is redirecting their anger onto different targets. That’s why Harris’s plan includes populist ideas to prevent evil corporations from raising the cost of housing and food.

Evil corporations are not actually to blame for the high cost of housing (which is about locally induced building restrictions) or food (which was caused by global factors that have since receded). But it’s easier to convince people of a simplistic solution than an unpopular truth.

The populist elements reflect the influence of the Democratic Party’s progressive wing. Mainstream economists are clinging to the hope that Harris doesn’t actually believe the demagoguery she is pitching, is only endorsing it because it polls well, and will allow Congress to bury these ideas if and when she wins. A positive aspect of this dynamic is that persuading Harris to endorse conceptually shaky but popular ideas is a big improvement from the left’s previous method of persuading her to endorse conceptually shaky ideas that are politically toxic.

Some news reports have described Harris’s plan as a way to “fight inflation.” Judged by that measure, it’s a bad plan. Harris’s campaign describes the proposals as a way to “Lower Costs for American Families.” Judged by that standard, it’s mostly good.