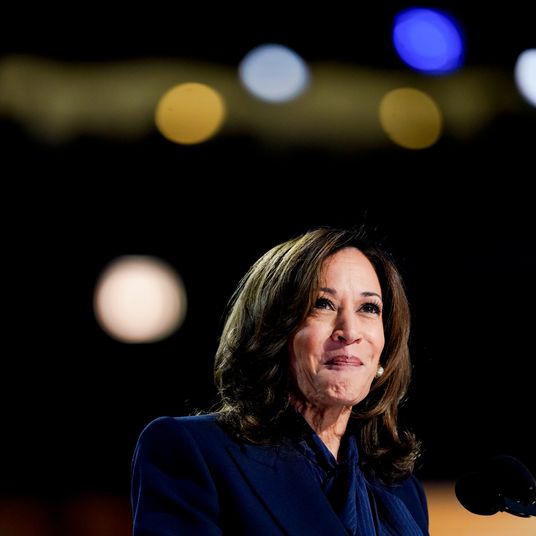

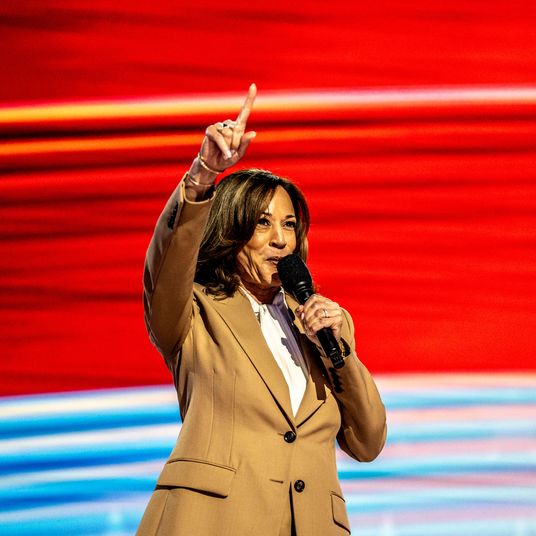

It didn’t take long for Kamala Harris’s campaign to come up with a plan to rebut Republicans’ most common attack on her that as Joe Biden’s “border czar,” she’s responsible for the southern border and the migrant surge. The vice-president hasn’t spent much time directly denying Donald Trump’s favorite accusation, which distorts her actual role working on the roots of migration in Central America. Instead, she’s been reaching back to a part of her career that hasn’t always been central to her political appeal: her time as California’s attorney general.

The message is unmistakable in one of the campaign’s new TV ads. “Kamala Harris has spent decades fighting violent crime,” it begins, over footage of Harris in her AG days. “As a border state prosecutor, she took on drug cartels and jailed gang members for smuggling weapons and drugs across the border.” The spot eventually closes: “Fixing the border is tough. So is Kamala Harris.”

That ad is in heavy rotation across the battleground states in the lead-up to the Democratic convention next week. It’s an indication of where Harris stands on an ongoing tactical debate near the top of her party over how to talk about immigration — and how worried she should be about Trump’s attacks on the issue.

Her preferred approach has been growing clearer since Republicans began zeroing in on a border-based attack just days into her candidacy. At her first extended campaign rally, a boisterous affair in Atlanta at the end of last month, Harris turned to the matter quickly. “I was the attorney general of a border state. In that job, I walked underground tunnels between the United States and Mexico on that border with law-enforcement officers. I went after transnational gangs, drug cartels, and human traffickers that came into our country illegally. I prosecuted them in case after case, and I won,” she said to peals of applause. Less than two weeks later, Future Forward, the main super PAC supporting her candidacy, debuted its own ad featuring old footage from her AG days. It opens: “She was tough enough to take on transnational gangs as a prosecutor.”

Harris’s reminders about her prosecutorial record aren’t limited to immigration. She’s also been bringing up her work on mortgage settlements with big banks and, of course, using her time as California’s top cop to frame the race more broadly as a contest between a prosecutor and a criminal. Yet, it’s immigration messaging where her party is still somewhat torn.

The biggest point of disagreement is how worried to be about the common GOP claims of Harris’s responsibility for the border. Blueprint, the polling and messaging group funded by megadonor Reid Hoffman, circulated a memo earlier this month concluding that the “border czar” attack — framing Harris as “an absolute disaster on immigration” with “open-border policies” — was Republicans’ most potent. Yet those close to Harris’s campaign have been significantly more skeptical. They say that in focus groups and polls, their target voters simply don’t believe Harris ran immigration policy for Biden, and that those who do believe it are solid GOP voters already, so not worth trying to persuade.

“We haven’t found any evidence at all that the fake ‘border czar’ meme, or whatever the heck it is, is effective with any voters,” said Matt Barreto, a Democratic pollster who focuses on Latino voters for the Harris campaign. “It’s just factually incorrect; they’re just making up some sort of label, and from there they have to explain what that even means. They’ve made up a false label that the American public is not familiar with.” Other Democrats close to the operation say that in focus groups, Harris is more readily associated with abortion and student-loan forgiveness than immigration.

As such, Harris’s camp has concluded that she should try to define the conversation over immigration rather than reply to Trump. Though Blueprint recommended a rebuttal message that focuses on Harris’s status as a child of immigrants as well as her understanding of the need for a better overall system, Harris’s actual argument about her time as AG sounds more like its second-favored option. And as the Democratic campaign has quickly adapted to having her, not Biden, as its standard-bearer, it has found that the most effective approach is to pair her AG talk with a reminder of the need for policy reform, especially a long-term pathway to citizenship. That’s why the campaign’s ad reminds voters that “as vice-president, she backed the toughest border control bill in decades, and as president she will hire thousands more border agents and crack down on fentanyl and human trafficking.” And it’s why at her rally in Atlanta, Harris promised to revive and sign the bipartisan border security bill that Trump blew up last year. While speaking in Arizona, the only battleground state on the border, a few days later, she assured 15,000 rallygoers that “we know our immigration system is broken and we know what it takes to fix it: comprehensive reform. That includes strong border security and an earned pathway to citizenship.”

Even if those close to Harris don’t buy that the near-ubiquitous GOP “border czar” attacks are especially dangerous for her, the topic is still sensitive. Harris entered the vice-presidency believing immigration policy was one of her strong suits after her work in California — she was AG during the surge of unaccompanied minors in 2014 — and in the Senate during Trump’s first term. Yet her popularity in the vice-presidency only began to drop when she first visited Central America in 2021 and dismissed questions from NBC’s Lester Holt about why she hadn’t visited the border. Within the White House, she was frustrated when her warning to migrants, “Do not come,” became a flash point, since she had just been repeating administration policy. At one point, she remained silent in a meeting with staff and a frustrated Biden, who demanded updates on the situation on the border. After, she told her own aides that she wanted it to be clear that she was not focused on the border but the origins of migration, and in the following months, some of her closest allies fumed that this issue — which she had not sought out as a portfolio item — was being treated as central to her work as vice-president.

Since the days after she became the party’s nominee, however, she and her confidants heard suggestions from her old friends and advisers to tell voters about her AG work on the border. One of her first trips in that job in 2011 was to Imperial County, where she convened state leaders and built out a task force to target transnational gangs, walked a drug-smuggling tunnel, and posed with border-enforcement agents while wearing a navy “POLICE” jacket. Her own focus as AG was on crime that came across the border, not border crossings themselves. But, explained Brian Brokaw, a former adviser who managed her AG campaigns, “she was elected AG by the narrowest of margins and she was immediately seen as the most vulnerable to the statewide elected officials. The biggest vulnerability she had was the opposition she’d faced from almost all of the state’s law-enforcement communities.” So trips like the first one to the border “became a very important part of her mission over the first term,” he said.

Democratic strategists aligned with her campaign say that in its early weeks, voters have responded positively to message-testing that educates them on her attorney general record. Immigration advocates in particular are watching her messaging closely, mostly to make sure she includes language about a pathway to citizenship in her appeal. But many close to Harris can’t help but remark on the massive shift in atmosphere around her prosecutorial record since the last time she ran for president, in 2019’s Democratic primary. Then, she spoke little of her time in the border tunnels and suggested entering the country without authorization should not be a criminal offense. She has since backed away from that position. “This is not the kind of material that ever would have flown in a primary in 2020,” said a longtime adviser. “It’s a reflection of the times having changed politically.”

It’s also a reflection of lessons Democrats have learned in the past year. Many saw Representative Tom Suozzi’s special-election victory on Long Island early this year as a model for how to talk about immigration, coming soon after Trump tanked the bipartisan border bill. Suozzi focused on supporting that bill and tightening immigration laws overall. To some strategists aligned with Harris’s campaign, that race was also yet more evidence that though Trump loves to talk about the border, his views are hardly broadly popular — they believe his family-separation policy cost him the 2018 midterms.

Now, they see Trump’s brand of border talk as primarily for his own base, not undecided voters. Voters overall often rank immigration as one of the more important ones they’re considering, but few senior Democrats believe the issue is likely to be the definitive one in battleground states outside of Arizona. In many states, Harris’s targeted voters “are focused more on what their mayors are doing within their cities than what’s going on on the border,” said Celinda Lake, a party pollster who does work with the campaign.

These voters, she continued, didn’t necessarily know Biden’s position on immigration and don’t know Harris’s. “They only know the Republican point of view,” so Harris’s job now is “more a question of filling in.” To many Democrats, the hope is that once she establishes her credibility on the matter, she can turn many voters’ attention to other issues, too. Nowhere has that played out more obviously than in Arizona. That’s where, two days after Harris spoke about the need for comprehensive immigration reform this month, organizers succeeded in getting a highly anticipated referendum on November’s ballot, on an issue where Democrats see a much clearer opportunity: the right to abortion.