This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was Tuesday afternoon at the United Center in Chicago, a few hours before back-to-back Obamas issued their impassioned calls to arms, and the famously sensible explanatory journalist Ezra Klein, who characteristically keeps his passions in check, didn’t have the right credentials to get into the arena. The Secret Service didn’t recognize the New York Times’ star “Opinion” writer and podcaster, who has had a bit of a glow-up lately with a salt-and-pepper beard and David Beckham–esque haircut, but eventually after we met up he was able to figure out how to get in to where he belonged. This is, after all, as much his convention as any journalist’s this time around, since its high-energy optimism turned on the fact that President Joe Biden no longer was leading the ticket. And, starting early this year, Klein platformed that Establishment desire, leading the coup-drumbeat.

It worked so well that Klein, 40, who has been an influential journalist for over half his life, is ready to come out from behind his computer, emerge from his podcast studio, and step into the spotlight. He tells me this is actually the first convention he’s attended since the Obama years. After spending his 20s writing lengthy blog posts on economics, he’s now become a tattooed middle-aged Brooklyn dad in Bonobos and sand-colored Air Force 1’s who goes to Burning Man, where he’s headed next week.

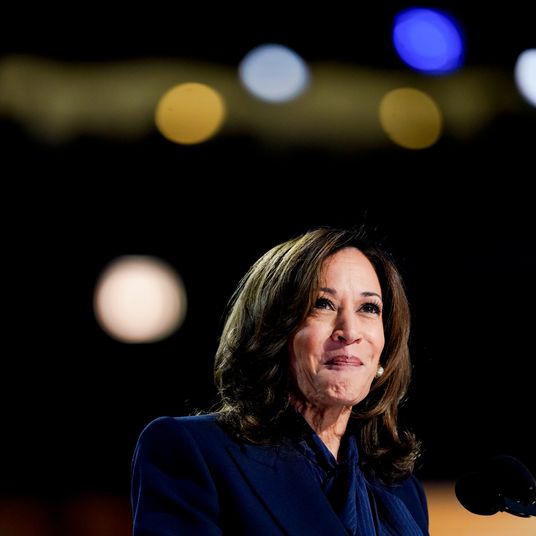

“The thing I got right this year wasn’t that Joe Biden was too old to run for reelection. Everyone knew that,” he told me in the back of a bar near his hotel in Downtown Chicago the night before. “The thing I got right this year was that the Democratic Party was an institution that still had decision-making capacity.” In February, Klein launched a series of podcasts and columns arguing that Biden should step aside. He also advocated for alternatives, like an open convention, and made the case for why Kamala Harris was underrated. Following his “prediction about the campaign” in February, as he later referred to it, Klein continued to take the pulse of the party. And while he didn’t get the open convention he was looking for, he did get what he called a “disorganized” mini-primary in the veepstakes — and played a role in the unofficial auditioning process, too, having Gretchen Whitmer and then Tim Walz on his show in the days leading up to Harris’s eventual pick. (He also invited Josh Shapiro on, but the Pennsylvania governor turned him down. “And look what happened,” Klein says, seemingly joking.) He says he’s “very uncomfortable” with the amount of attention he’s received, though he seems to be enjoying it just fine, even if Semafor was picking on him a bit for being too cozy with top-echelon Dems with a piece posted August 18 titled “The New York Times’ Ezra Klein Problem.”

There is a historical tension between the newsroom and “Opinion” side at the Times, one that Klein doesn’t believe is all that useful. “I think of my work as primarily reported,” he says. “My line for a very long time back when I was at the Washington Post,” he says, “was that the division between the news and opinion sides made it too hard for the news side to tell the truth and too easy for the opinion side to bullshit.” He adds, “I don’t really think my show’s lineage, so to speak, is actually inside that opinion-news divide.”

Still, the Times works hard to maintain its journalistic propriety. Following the debate, but prior to Biden’s dropping out, Klein wanted to have Times politics reporter and The Run-Up host Astead Herndon on his show to talk about Harris. But executive editor Joe Kahn shut it down. This was around the time the paper’s own editorial board had joined the chorus of calls for Biden to step aside, a moment when newsroom leaders felt the need to reinforce the division between the newsroom and “Opinion” side. “Newsroom people get resentful as he veers more into newsmaking,” one Times staffer noted. Said another, “I think he only becomes more powerful over time, since I’d argue the influence of the Times editorial board (and all ed boards, really) has waned over the course of the rise of the internet and social.”

But in general, Klein’s star status doesn’t seem to be a problem at all for the Gray Lady, which runs full-page advertisements for The Ezra Klein Show in the paper and is building out a video dimension to the podcast. He recently interviewed Nancy Pelosi in a room in the middle of Times HQ, footage of which prompted speculation — among media folk, Brooklyn-mom group chats, etc. — about that glow-up. He dismisses speculation that he now has a stylist — he’s a man who respects the experts, after all — though notes that he’s been determined to spend “some time this year upgrading my wardrobe and my style, but it’s a thing that has not happened in my mind yet.”

Klein was not the first pundit to urge the president against running for reelection. Maureen Dowd said as much in the summer of 2022 (as did Mark Leibovich); David Ignatius, too, in September 2023. But what made Klein more influential is “he is seen by many party elites as much more of a partisan figure, instead of just a columnist,” Axios political correspondent Alex Thompson told me. “It was someone pretty deeply steeped in the Democratic Party basically being the first one to break the taboo.” That The Ezra Klein Show is dominating the charts or has a cult following is not new, but the sense that he is plugged into the inner workings of the Democratic Party has imbued the podcast with greater importance.

“I mean, some things happened in public. It wasn’t all just behind-the-scenes reporting,” Klein says, between sips of a mezcal-soda at the hotel bar. “But I try to pay attention to who people pay attention to, and who’s earned that respect and credibility inside the caucus — or inside or among other donors, or among strategists. And you can feel those things.”

Every election cycle at the Times has a face, and Klein, despite being an “Opinion” writer, is this year’s. “I don’t think anyone notable’s behavior would change because of his podcast,” a Democratic strategist told me. But where he deserves credit, they said, is “helping to initiate that conversation a while ago” and keeping it in the media long after.

“This was not a fun process,” Klein says. “This was a really wrenching thing the party had to go through.” As for his role in it, heavy is the head. “Look, I recognize that in the rare moments when people want to say you’re right about something, you should agree and accept it, but it also feels like it always pins a target on your back,” he say. Klein seems broken up, though unsurprised, about the bridges he’s burned. “When I did the February piece, I recognized it was going to fuck up a lot of my relationships in the Biden White House.” Still, he was “aghast” when I told him I’d heard that there was conspiratorial chatter among Biden officials after Klein’s piece, wondering who — someone in Obama’s camp? — had planted the idea with Klein. “I’m actually shocked to hear anybody would think that. That’s so dumb,” he says. “The only thing happening here was saying what everybody was seeing.”

It was through reporting, he says, that he came to that conclusion. “I talked to people and I understood that they could imagine that Joe Biden shouldn’t run, but they couldn’t imagine what would lead him to step aside and what to do if he did,” he says, noting he was frustrated by the “sense that this was going to be a stable situation — that people were not going to need alternatives.” He also felt he owed it to his listeners. “I don’t think people pay a lot of attention to the mechanics of nominating processes,” he says. “I was just trying to make people aware that this wasn’t done.”

Klein tells me he’s interested to see if this moment of collective action changes the Democratic Party going forward. “Institutions have muscles, and the muscles atrophy when they’re not used, and they strengthen when they are used, and the Democratic Party did something collectively. It’s really unusual, functionally unknown about American politics.” The party proved itself “beyond the ambitions of any one person,” he says. “It’s not that I think the Democratic Party is going to start knocking its candidates off or something, but it just learned it can act in a way that I could tell you for a fact its members did not think they could.”

Talking to Klein can feel, at times, like listening to his show. He’ll casually go on a tangent about child-care policy or recall a cross-national study, and then he’ll become a normal person again, talking about the challenge of juggling his professional and personal life, married to Atlantic journalist Annie Lowrey, with two kids, living in Brooklyn.

“I think I’m an interesting person on my podcast. I often wonder why I’m not more interesting at home,” he says. “Sometimes I think, Does my family get the best version of me? And the answer is often ‘no.’” I ask him what he does for fun. “A mix of very quiet and very loud,” he says. “I spend a lot of time quietly reading. I have very deep friendships. I go to a lot of shows.” This will not be his first time going to Burning Man.

He has been covering politics since he was 18, cutting his teeth as a policy blogger. He moved the blog from Typepad to the American Prospect in 2007, when he was 23. Then he went to the Washington Post, where he ran the popular Wonkblog. After five years, he left to co-found Vox, the website that became the namesake of the multi-brand digital-media company that today owns New York Magazine, until departing for the Times in 2020. His popular interview podcast, The Ezra Klein Show, followed him there.

He considered going another route: selling his podcast to Spotify, starting a Substack. “I sometimes feel like a dumbass who’s left a ton of money on the table,” he admits. But he likes being part of institutions and seems, in a vaguely messianic way, to see it as his duty to support them. “It’s true that I could make more money doing this independently, but if all the people who do what I do decide to go and capture all of their revenue themselves, then what happens to all the parts of the industry that are frankly more important than what I do, but are not self-sustaining in that way?” he says, citing investigative and foreign reporting among the beats that haven’t quite figured out the newsletter format. It seems to be a mutually beneficial relationship: “The Times is a unique power,” he says. “If I had done the same pieces from Substack, would it have mattered?”

Going to the Times meant he didn’t have to manage anymore — “It feels almost decadent to only really have to worry about my own work,” he says — and could focus on what he wanted to do, as opposed to the biggest stories that Vox needed its biggest voices to cover. “That allows me to follow my own interests with a lot more authenticity than I would be able to bring otherwise,” he says. What some people love about Klein and what some people hate about him is that he makes himself a mini-expert on everything, dipping in and out of topics, from AI to wellness to the Russia-Ukraine war. He has a Zadie Smith interview coming up and will soon welcome back Richard Powers to the show. “Those are things that bring me a huge amount of joy, and it is really hard to imagine what else I could do that would allow me to explore my own interests broadly.”

“He’s an influential voice but also generationally unique,” said Obama senior adviser Eric Schultz, citing traditional media’s fight for attention and relevance in an ecosystem filled with tweets and clips and trolling. Klein has “found a sweet spot that I don’t think anyone else has been able to replicate. It’s like what the Sunday shows used to be,” said Schultz. “Now they’re consumed by the blow-by-blow, and Ezra is having the thoughtful conversations.”

Klein, who grew up in Orange County, California, moved from San Francisco to Park Slope, then Gowanus, a year ago to be closer to his wife’s family. The redwoods are still close to his heart, literally, as he has a tattoo of them on his shoulder. He recently added a second tattoo, a typewriter-font “Is That So?” printed on his inner bicep. “A reminder to not believe what you think,” he says, when I ask him what it means to him. “Sometimes people see it and they think of it as outwardly focused, but it’s inwardly focused,” says Klein. “The easiest person to convince of anything is yourself. And it connects to small Zen stories that I like.” It took him a while, he says, to get over the belief that you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery if you have tattoos, which he claims is “a complete myth” and tells me that I can read all about it in a Times article.

This post-glow-up Klein might seem like he’s ready to mingle at the joy-filled late-night celeb-packed party-ready DNC. But he says he’s not really planning on hitting the town (and I didn’t see him out, either). His first night in town was spent at dinner with his editor and a member of Congress and then in his hotel room, where he watched the speeches. On Tuesday, he watched the speeches from the floor — where, according to his boss, Katie Kingsbury, with whom he was standing, an usher recognized him but not her — but didn’t hit any afters after. “I doubt I’ll go to anything,” he texted me, when I asked him his party plans for the rest of the convention. “Going to watch from the floor each night then I record fairly early in the morning. So no real social calendar really,” he said. “Work, work, work.”

Correction: A previous version of this story attributed a column by David Ignatius to Paul Krugman. Also, this story has been updated to reflect the correct date of a Semafor story.

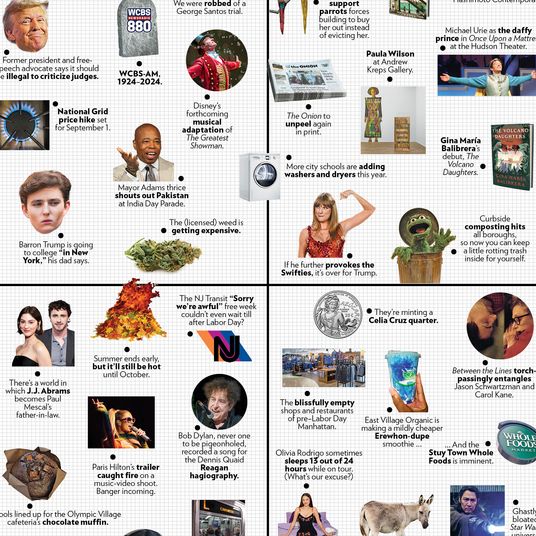

More on the 2024 DNC

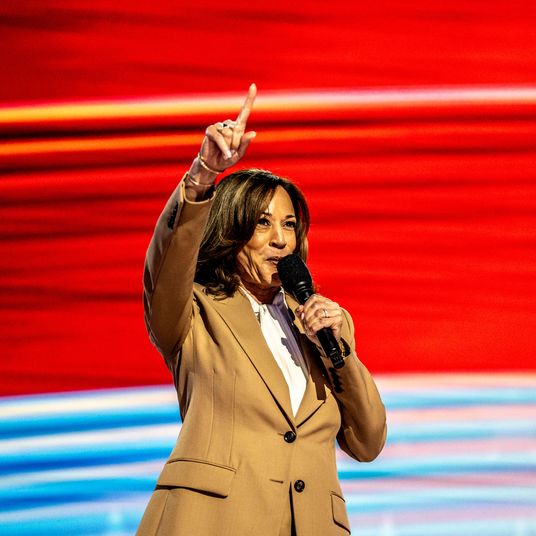

- Kamala Harris and the New Politics of Joy

- Producing Chicago

- Photos: The Vibe-Shifted Democratic Convention