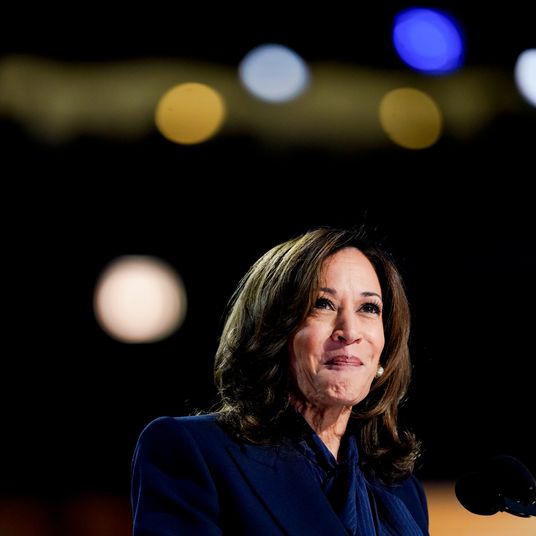

Barack Obama listened with interest when Kamala Harris dropped by his office in Washington to make the case for her presidential candidacy and to ask for his advice. There was an endless stream of commentary comparing the two — both Black politicians with immigrant parents who reside ideologically in the party’s center. He wasn’t so sure about the parallels, but he was desperate to vanquish Donald Trump and he’d made no secret of his belief that Harris could represent the future of the Democratic Party. By the time she walked out, Obama could clearly see her political promise, but thought she needed to figure out how exactly she would appeal to the vast swaths of voters who’d never heard of her.

But that was 2019. What a difference five years makes.

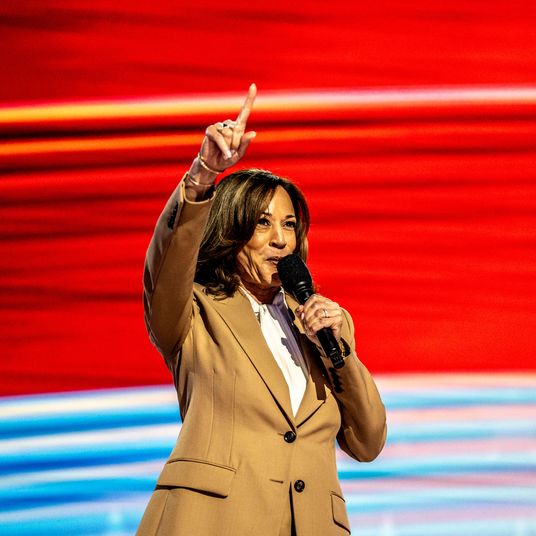

Today, Obama is all in for Harris. The two have spoken multiple times in the weeks since Joe Biden decided to stand down, according to multiple Democrats briefed on the campaign and Obama’s activities this summer. Sitting in Martha’s Vineyard, he’s fielded her calls about Biden’s decision, her campaign messaging, and her running-mate options. (Obama didn’t push for any particular candidate but emphasized to Harris the importance of finding a governing partner with whom she felt comfortable.) Obama, these people say, is so far impressed with Harris’s blockbuster campaign start, though the always-cautious ex-president has warned political allies that her operation still has significant work to do before it can feel confident about beating Trump. To that end, Obama has been in touch with Harris’s top advisers — a growing number of whom used to work for him — as they map out her strategy for the fall, offering help and input. On Tuesday, both Barack and Michelle Obama will give Harris their most prominent boost yet during a pair of Democratic National Convention appearances in Chicago that they hope will set a unifying tone for the final weeks of the campaign.

Both Obamas have spoken to friends about their appreciation of the fact that Harris was an early supporter. But though the two pols met occasionally through the years, their respective rises were hardly tied together and their relationship has hardly always been substantial.

Harris and Obama first met two decades ago, when she was the San Francisco district attorney and he was an Illinois state senator on the rise campaigning for a Senate seat. That meeting wasn’t as memorable for Harris as when, four years later, she flew to frigid Iowa to knock on doors for Obama’s presidential campaign. The pair stayed in occasional touch once Obama became president, and he raised money for her 2010 attorney-general race — and in 2013 had to apologize for calling her “the best-looking attorney general in the country” at a San Francisco fundraiser. Still, their political trajectories never quite met: When he asked if she wanted to be considered to replace Eric Holder as attorney general in 2015, she demurred with an upcoming Senate run, and her long-term future, in mind. Obama paid little attention to Harris’s subsequent campaign, but he brought her name up multiple times when interviewers asked him who might represent Democrats’ future after Trump won in 2016.

Obama watched Harris’s Senate work closely during his self-imposed exile from daily politics; although he briefly became interested in her 2020 campaign, the common pundit comparisons between the two struck him as superficial. (Their political messages, let alone policy emphases and campaign approaches, had little in common.) Still, he counseled Biden through his running-mate selection process and supported his choice of Harris despite her poor showing in the primaries.

They spoke only sporadically once Harris became VP, even though they shared many donors and influential fans, and their political inner orbits overlapped only slightly. A few of Harris’s friends had gone to work for Obama’s campaigns and administration through the years — they shared a pollster, David Binder — but most of her allies, donors, and consultants were based in California and his were from Chicago and Washington. So many plugged-in Democrats read her decision to hire a squad of Obama allies to run a revamped Biden campaign as a statement of intent that she would hew to Obama’s political strategy more than ever before.

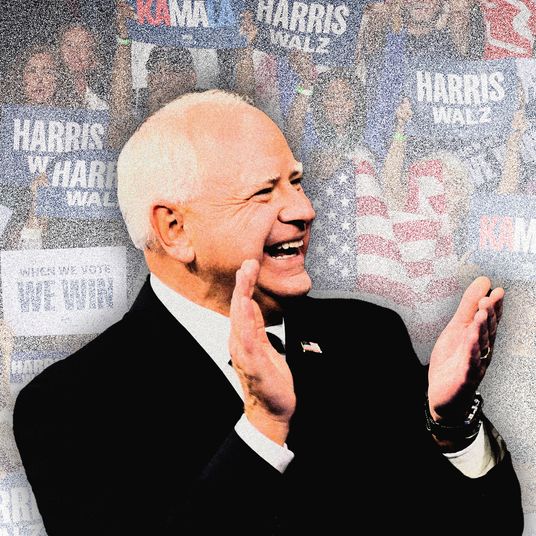

David Plouffe, Obama’s 2008 campaign manager who remains close to the ex-president, was the most prominent hire. (Obama encouraged him to join.) But he was not alone. Stephanie Cutter, a former deputy campaign manager and strategist, and Mitch Stewart, an organizing operative who remained close to Obama after he left office, are also new to the team, as is former communications director Jennifer Palmieri, who is helping Harris’s husband, Doug Emhoff. Other close Obama aides have risen in prominence since Harris ascended on the ticket: She has been relying on Adam Frankel, a former speechwriter, and brought Binder, the pollster, onto the campaign, too. Even before hiring her new team, Harris tapped Holder, a close Obama friend, to run the vetting process as she searched for a running mate. Obama has watched her hiring process closely, and he still speaks regularly with Jen O’Malley Dillon, the campaign chair who had previously been one of his own political advisers, and has committed to cutting more videos for Harris.

What remains to be seen is how, exactly, Obamaism itself shapes Harris’s appeal. She has already been much more active on the trail and focused on a vision for the future than Biden had been but has so far been light on a governing agenda or policy specifics. She and Obama are both treading carefully around the question of what it means to pivot aggressively to the future in her public messaging; Harris’s quick embrace of the Obamans struck some clued-in Democrats as an implicit criticism of the current president or at least his political operation. Plouffe, for one, has not always seen eye-to-eye with top Biden advisers, and Biden has often privately blamed the ex-president’s advisers for encouraging Obama to push him out of the 2016 race. Biden remains frustrated by the way his defenestration played out, making it clear to friends that he is especially unamused about what he perceives to be Obama’s role in it — whether that was actively discussing his ouster or simply declining to defend him more. (Obama was not orchestrating the push, but he did speak with Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer as pressure mounted on Biden.)

Over and over, Obama has reminded those who ask that the race is likely to be close and that Democrats cannot afford to be stuck in rounds of internal fighting, not when there are just three months until Election Day. One person who’s spoken with the former president about the election was matter-of-fact about Harris’s campaign: “In a sprint election, she’s our horse.”

More on the 2024 DNC

- Kamala Harris and the New Politics of Joy

- Producing Chicago

- Photos: The Vibe-Shifted Democratic Convention